achieving social and economic inclusion: from segregation to 'employment first'

Law Reform and Public Policy Series

Canadian Association for Community Living

June 2011

Diversity Includes.

| Achieving Social and Economic Inclusion: From Segregation to 'Employment First'

First Published 2011

By Canadian Association for Community Living

Toronto, Ontario

© Canadian Association for Community Living. All rights reserved.

Project Director: Michael Bach

Senior Researcher: Tyler Hnatuk

Design: is five Communications

Printed and bound in Toronto by is five Communications.

ISBN: 0-919070-15-9

For information or copies contact:

Canadian Association for Community Living

Kinsmen Building, 4700 Keele St.

North York, Ontario

M3J 1P3

Tel: 416 661 9611

Email: inform@cacl.ca

Website: www.cacl.ca

Founded in 1958, the Canadian Association for Community Living (CACL) is a national federation of over 40,000 individual members, 400 local associations, and 13 Provincial/Territorial Associations for Community Living.

We are people with intellectual disabilities, their families and supporters working together to ensure that all people:

- have the same rights and access to choice, services and supports as all other persons;

- have the same opportunities as others to live in freedom and dignity, and have the needed supports to do so;

- are able to articulate and realize their aspirations and their rights.

To advance its mission CACL and its Provincial/Territorial Associations for Community Living have adopted a 10-year ‘2020 Agenda’ for change to work with Canadians, governments, the public and private sectors to make a difference in the lives of Canadians with intellectual disabilities. For more information visit us at www.cacl.ca.

Contents

Acknowledgements

This research study was prepared by the Canadian Association or Community Living. Project director was Michael Bach. Tyler Hnatuk was the senior researcher and drafted the report.

The authors and the Canadian Association for Community Living wish to thank all of those who participated in the project as key informants. Special acknowledgement is made to Cameron Crawford, President of the Institute for Research on Inclusion and Society and Bob Vansickle of the Ontario Disability Employment Network who provided comments on early drafts of this report. Grateful acknowledgement is made to Susan B.

Parker, currently a senior executive working in disability policy development in the U.S. government, who provided valuable insight on and general information about employment first initiatives in the United States.

The Canadian Association for Community Living gratefully acknowledges the financial contribution to the research from the Government of Canada through the Department of Human Resources and Skills Development, Office for Disability Issues. The findings and statements in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Canada.

Preface

I am very pleased to introduce the first study in the ‘Law Reform and Public Policy Series’ of the Canadian Association for Community Living (CACL), and to do so for a study about one of the most urgent and pressing issues we are facing. How do we ensure social and economic inclusion for this and future generations of young people with intellectual disabilities who are transitioning to adulthood?

The employment rate of people with intellectual disabilities languishes at only 25-30%. The resulting poverty rate shows the impact. Seventy-five percent of working age adults with intellectual disabilities live in poverty, and the costs in social isolation, victimization, poor health and untapped potential are enormous.

Our Associations across Canada have built supports and services over the past fifty-plus years that are making a huge difference in building inclusive communities from coast-to-coast-to-coast. However, for far too many young people some approaches still prevalent in communities across Canada are a ‘dead- end.’ Having made some real headway in inclusive education, young people with intellectual disabilities are leaving school to sit at home, or spend their days in an activity centre, sheltered workshop, or enclave workplace designed only for this group. Not only economically exploitative in many cases, these approaches keep expectations of young people, their families and community members low. Potential is lost, and segregation becomes the norm.

At the same time, we have impressive examples of supporting people with intellectual disabilities to go on to inclusive post-secondary training and education, to choose careers, make contributions, and earn decent and living wages. A range of supported employment, self-employment, and other options are tested, and well-documented. We have examples of how to transition out of sheltered approaches into labour market inclusive options. There is knowledge, leadership and capacity to build upon to make good jobs a reality for Canadians with intellectual disabilities at the same rate as the rest of the population. We know it can be done. It’s time to scale up what we know is good practice, into federal and provincial/territorial policy and programs to incentivize these practices and make them operational across the board.

We hope this study contributes to an active dialogue among disability organizations, community service providers, employers and governments about how to make ‘employment first’ a reality for Canadians with intellectual disabilities.

Lorraine Silliphant,

Chair, Law Reform and Public Policy Advisory Committee Canadian Association for Community Living

Foreword

Over 50 years ago parents started meeting in communities across Canada to share their concerns that their sons and daughters with intellectual disabilities were not being given the opportunities to fulfill their potential; that they had no valued place in society. Denied access to public education that their own tax dollars were helping to fund parents began demanding a different future, began making a claim on governments and society for what we now call full citizenship and inclusion.

These courageous parents faced closed doors and incredulity at every turn. So they took matters into their own hands, and in the name of a more promising future for their children, they began their own schools. As children grew into young adults, and workplaces and the labour market remained similarly closed to the possibilities, parents formed local associations and created activity centres and sheltered workshops. Their adult children had somewhere to go during the day, the chance to learn some life and social skills they had been unable to develop because of exclusion in their early years, and the chance for some respite for their parents. Through the 1950s and 1060s our associations for community living built an impressive infrastructure of special education, sheltered workshops and activity centres, and residential care arrangements, inspired by a vision that people with intellectual disabilities were as deserving of support and a chance in life as anyone else.

By the 1970s, there were some voices among families and leaders of our movement which began to challenge whether this was enough. Was our sole purpose to build this kind of service capacity, on the assumption that since so many doors were closed – and people didn’t seem to belong in regular education, or works places, or with access to regular housing markets – all that people with intellectual disabilities deserved were special, separate services? As a human rights discourse began to grow, these assumptions were questioned. Over the last thirty years, we have worked to ensure that people with ntellectual disabilities take their rightful place in society, alongside their brothers and sisters, classmates, peers, co-workers, and other citizens. Our vision of belonging, inclusion, dignity and equal respect has most recently been expressed in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, ratified by Canada in 2010, and which recognizes in Article 27 “the right of persons with disabilities to work, on an equal basis with others; this includes the right to the opportunity to gain a living by work freely chosen or accepted in a labour market and work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities.”

Our challenge now is that our vision outstrips the service capacity we have built. It’s time to catch up with ourselves. The Canadian Association for Community Living undertook this study to look at how we might chart a path from the infrastructure we have collectively built for sheltered workshops and activity centres, to supporting people to access the labour market and fully inclusive workplaces like other Canadians, within the context of what we have termed an ‘employment first’ policy framework. Some visionary local associations and leaders are showing the way forward. We have immense know- how in local associations across the country. Our mission must now be to turn this knowledge and infrastructure we have built in the direction of securing social and economic inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities.

We hope this study and its recommendations for the federal and provincial/territorial governments to take leadership for an ‘employment first’ policy and program approach for labour market inclusion of youth and adults with intellectual disabilities gets traction. We look forward to working with all our partners in supporting and resourcing the necessary local leadership and capacity to make it a reality.

Michael Bach

Executive Vice-President Canadian Association for Community Living

Executive Summary

This study examines effective policies and practices for moving from provision of sheltered employment and enclave work options for working age adults with intellectual disabilities to supports that enable labour market inclusion.

People with intellectual disabilities in Canada face one of the lowest rates of employment at just over 25%. Yet the research is clear that people with intellectual disabilities want to work at real jobs for real pay. Where effective measures to encourage labour market inclusion have been put in place, employment rates in integrated employment of people receiving disability supports are as high as 87%.

Although enrollments in sheltered workshops are slowly declining, sheltered workshops, segregated day programming and enclave based employment persist as a dominant model of support for this group in Canada. With below minimum wage compensation, they constitute a form of financial exploitation and social and economic exclusion with substantially lower quality of life outcomes than employment focused approaches.

Internationally there is a move away from sheltered workshops for these reasons and toward supported employment and related approaches that show positive employment outcomes. The UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities recognizes the right of people with disabilities to “the opportunity to gain a living by work freely chosen or accepted in a labour market and work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities.” In the U.S. there is a major shift toward states adopting “Employment First” policies for the services provided to people with intellectual disabilities.

Labour market inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities, compared to sheltered employment, segregated day services and other sheltered models, shows higher outcomes in quality of life, incomes and benefits, individual autonomy, individualization of services, individual and family preferences, social inclusion, personal satisfaction and cost efficiency.

While there was a significant effort to close sheltered workshops and move toward supported employment in the 1970’s and 1980’s, this progress has stalled. Efforts at transition from sheltered workshops appear to have more often resulted in programs oriented toward social and community integration or to employment supports that still retain an enclave model rather than labour market inclusion. Many services that continue to operate on a sheltered workshop model have reframed their activities as “training programs,” “life skills,” and “work preparation” but are not demonstrating employment outcomes. Being clear about what labour market inclusion and employment are, and what they are not, is an essential first step for policy and program initiatives aimed at increasing labour market inclusion for this group.

Factors that enable or present barriers to transitions to labour market inclusion are identified in this study through data from interviews with key informants in the field of disability employment supports, policy officials in provincial and territorial government and policy research experts and research literature. Barriers include: predominance and continued investment in sheltered and enclave models; emphasis of disability day supports on non- employment activities; and the lack of a coherent policy and program framework for funding and delivery of employment supports to people with intellectual disabilities. Key factors enabling transition include: making ‘Employment First’ the policy and program goal in employment supports; awareness and leadership among parents and educators; building capacity of service providers for Employment First approaches; ensuring availability of long-term employment supports; facilitating knowledge transfer and demonstration projects; addressing disincentives in income security systems; and focusing on employer needs.

Policy conditions to make an effective transition from sheltered workshops and day programs to Employment First approaches include: (1) an “Employment First” policy framework that includes clear definitions of employment and principles, cross-departmental and inter- jurisdictional policy and ongoing processes of capacity development at the local level; (2) Funding that includes investments into a coherent community-based delivery system, local community capacity building, demonstration initiatives, training and technical support and employer capacity; (3) Data and reporting on labour market inclusion with clearly defined employment outcomes for employment supports; (4) Knowledge transfer about effective employment practices; and, (5) Removing disincentives to labour force participation in income security systems.

Three main policy directions for the federal government are proposed: (1) Create a targeted fund in the Opportunities Fund for Persons with Disabilities to develop a national partnership and local demonstration initiatives focused on transitioning from sheltered workshop and day programs to Employment First programming; (2) Fund new priorities within the federal- provincial Multilateral Framework Agreement for Labour Market Agreements for Persons with Disabilities, and the federal-provincial/territorial Labour Market Agreements for this purpose; and (3) Develop a data strategy to track labour market inclusion outcomes.

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to examine effective policies and practices for moving from provision of sheltered employment and enclave work options for working age adults with intellectual disabilities to labour market inclusion. This group faces one of the lowest rates of employment at just over 25%. Historically denied full access to education, people with intellectual disabilities continue to experience a wide range of barriers to successful inclusion in the labour market and workplaces. These include ineffective school-to-work transitions, barriers to post-secondary training and certification, lack of supports and on the job accommodations, lack of confidence and expectation by parents, support persons and employers, inaccessible or unavailable transportation, outmoded training options such as sheltered workshops that limit participation, and lack of access to self-employment and business development supports, to name some of the key factors.

This study focuses on best practices that enable working age adults who are participating in, or who might otherwise participate in, sheltered workshops and life skills programs to transition to competitive employment, inclusive workplaces and/or self- employment. The focus is on the factors that enable a trajectory of access to inclusive labour markets and competitive employment, rather than to sheltered employment; and that enables transition from sheltered to mainstream employment.

The rationale for this research is that sheltered workshops provide sub-standard wages, and reinforce social and economic exclusion, including the stereotype that people with intellectual disabilities are unable to participate fully in the labour market due to the nature of their disability. Some have argued that sheltered workshops provide belonging, social participation, and respite for family members caring for working age adults with intellectual disabilities. While these are important functions, other models of employment support clearly demonstrate that labour market and workplace inclusion is possible for this group, and secures better quality of life outcomes. Moreover,continued segregating and exclusionary practices of this nature appear to be in contravention of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which Canada ratified in March 2010.

The objectives of the research study were to:

- Document best practices for inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities in the labour market

- Provide details regarding structure, content, processes and outcomes of integration practices that have transformed outdated workplace models into inclusive workplaces

- Analyze content of existing evaluations, policy documents, governance and management structures

- Identify the policy conditions that support these transitions

The report is divided into three main sections:

Section I provides a brief overview of research methods.

Section II presents key findings including: overview of the population; concepts associated in the literature with the policy goal of labour market inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities; effectiveness of a range of approaches to employment supports; and factors and good practice in enabling transitions from sheltered employment to labour market inclusion.

Section III assesses the current policy framework, and identifies a set of policy conditions that would enable effective transition.

Section IV outlines directions for future research on implementing these conditions.

I. Research Methods

The principal research methods used for this study consist of (1) literature review of Canadian and select international sources and (2) interviews with key informants.

The literature review consisted of published reports and studies as well as ‘grey literature’ with a focus on policy and program descriptions, policy and program evaluations, academic research studies on the topics identified and case study materials.

Key informant interviews were conducted with policy officials from provincial territorial governments, policy researchers, employment support providers and representatives from provincial and territorial Associations for Community Living and provincial networks of employment support providers. In total, 23 interviews with key informants were conducted with representation in 7 provinces and territories.

II. Findings

A. The Population

Definition and prevalence of intellectual disability

- The terms ‘intellectual disability’, ‘intellectual disabilities’ and ‘developmental disability’ are often used interchangeably. Intellectual disability is defined as significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and in adaptive behavior in everyday social and practical skills, with onset before age 18. 1

- Statistics Canada’s 2006 Participation and Activity Limitation Survey (PALS) estimates 0.6 per cent of the working-age population (15 to 64 years) have intellectual disabilities. However, this particular sample was weighted to those with severe or very severe disabilities— estimated with the 2006 sample to be 75% of the population with intellectual disabilities. The same survey shows that only 40% of people with other disabilities have severe or very severe disabilities.

- According to standard prevalence estimates, the total population of people with intellectual disabilities includes a much larger proportion of people with mild disabilities, and is in the range of one to three per cent (Horwitz et al. 2000; Bradley et al. 2002). As findings of the Surgeon General of the United States indicate, the condition of most people with intellectual disabilities is “relatively mild, and once they leave school, they disappear into larger communities, untracked in major national data sets” (2002, xii).

- A median prevalence rate of 2% would mean that there are approximately 473,450 working age adults with intellectual disabilities in Canada, inclusive of the 129,000 people identified through the 2006 PALS data primarily as ‘severely’ or ‘very severely’ disabled. 2

Labour force statistics and socioeconomic status

- According to PALS 2006, only 26.1% of working-age people with intellectual disabilities are employed, and almost 40% have never worked. This compares with a 53% employment rate of people with disabilities, and 75% employment rate of persons who do not have disabilities. This figure is in the same very low region of labour force participation estimated in the 1991 Health and Activity Limitations Survey which included a larger proportion of those with ‘mild’ intellectual disabilities. 3

- The average earnings of people with intellectual disabilities employed at some point in 2005 were $18,172 and nearly half received provincial social assistance. Average earnings of adults with disabilities as a whole were $29,669 and for people without disabilities, $37,9444.

Participation in postsecondary training and education

- The education level of adults (15 years and older) with intellectual disabilities tends to be low overall, with 66% having attained less than high school graduation compared with 25% of other people with disabilities.

- Over 60% of working-age people with intellectual disabilities have attended special education, defined as a special education school or special education classes in a regular school. Only 12.7% of other people with disabilities have attended special education.

- Only 35% of people with intellectual disabilities have taken any training to learn new or improve existing employment-related skills.

B. Labour market and social and economic inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities: key concepts

This study is guided by the policy goal of labour market inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities who have been, or are likely to be, in segregated work environments. A select review of literature suggests the following conceptual approach for applying the policy goal to this group.

Labour market inclusion

Promoting an ‘inclusive labour market’ is a guiding labour market policy goal reflected in federal-provincial Labour Market Agreements and the mission of Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. While there is no concise definition of this concept, as a policy goal it has been associated in the literature with a number of objectives:

- advancing employability of traditionally disadvantaged groups through multi-dimensional ‘active’ measures. A recent review of such measures for working-age persons with disabilities in the European context shows growing adoption internationally of labour market inclusion as a policy goal and active employment measures for this group (Eichhorst 2010);

- addressing labour market segmentation by providing greater social investments for child care, home care, transportation, etc. for groups most at risk of under-representation and ‘precarious’ employment (Jackson 2003);

- increasing short and long-term productivity, economic competitiveness and more equal labour market access through social investment in ‘productivity enhancing services across the lifecourse (care for dependents; education, training and lifelong learning; and health maintenance) (Bernard & Boucher 2007);

- reconciling twin objectives of flexibility in the labour market to promote transitions, mobility and competitiveness; with economic security for workers and families – through ‘flexicurity’ (Bernard and Lebel 2009; European Commission 2007).

In achieving these objectives for working-age adults with intellectual disabilities, particular account needs to be taken of how supports, training and employment programs targeted specifically to this group have to a large extent been based on a segregated model. Research has shown positive outcomes of labour market inclusion in comparison to sheltered employment for people with intellectual disabilities in terms of improved quality of life, income and benefits, adaptive behavior, social inclusion, responsiveness to personal choice and individual need; as well as being more cost-effective (National Disability Rights Network 2011; Migliore 2007; Zimmerman 2008; Beyer et al., 2010; Eggleton 1999; McGaughey and Mank 2001).

Taking this context into account, and the policy objectives identified above, formulating the policy goal of labour market inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities should incorporate four main elements:

- access to socially inclusive training and education opportunities according to individual employment and career goals;

- participation in labour markets generally available to the labour force, and not based on disability;

- supports that enable a person to participate in employment-related training and education, workplaces and labour markets, and to make transitions within and between them (including disability-related supports, care for dependents, needed health care, transportation, and lifelong learning opportunities);

- economic security through a living wage and benefits.

Community integration

‘Community integration’ is a key dimension of employment-related options for people with intellectual disabilities because of the social exclusion this group has historically faced, often from a very early age. For many, becoming involved and visible in community – whether their local community or communities of interest beyond disability-identified communities – is an important step in shedding some of the usual stereotypes that have been applied to people with intellectual disabilities and underlay their social and economic exclusion.

However, the literature points to an important distinction between community integration or presence and community participation for people with intellectual disabilities (Bigby and Fyffe 2010; Clement and Bigby 2008; O’Brien 1987). Placement in community-based settings from congregate residential facilities, or from sheltered environments can be an important step in the process of fuller inclusion. Presence does not necessarily lead to participation and inclusion. Often people with intellectual disabilities, who are placed in community-based activities, but without personal relationships in the broader community, end up inhabiting distinct ‘social spaces.’ Researchers suggest this outcome calls for a more focused effort by the service sector and governments on ‘inclusion work’ and inclusion as a social change project (Wilson and Jenkin 2010).

Social and economic inclusion

There is a growing recognition of the link between labour market policy and social and economic inclusion and exclusion (Crawford 2003). For example, greater labour force participation and access can be achieved through precarious labour markets that result only in low-paid, insecure jobs. However, such access can leave a person with inadequate income and benefits, or personal resources or time to participate and be valued in the social dimensions of community life, and lead effectively to social isolation (Jackson 2003).

While it is used as a policy goal linked to labour market inclusion, researchers have found that the concept of social inclusion has not been adequately conceptualized in empirical studies of people with intellectual disabilities (Bigby 2010; Verdonschot et al 2009). In reviewing this literature, Bigby and Fyffe (2010) suggest that core components of social inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities are: development of a wide range of personal relationships across all aspects of community life, the building of social networks and enjoying a variety of social interactions with non-disabled others in which people are valued for their unique identities and contributions. They also identify a sense of belonging as another key component.

Drawing on this diverse literature, social and economic inclusion can be identified as a key objective of labour market policy for people with intellectual disabilities. Its main elements can be summarized as follows:

- being valued and welcomed by peers in the workplace and community;

- having a range of personal relationships – across domains of community life – that expand one’s social networks;

- experience of belonging

- opportunity to develop, pursue and achieve personal career goals, and to make valued economic contributions;

- current and future economic security.

These concepts are drawn upon in the following analysis of employment supports and programs available to working-age people with intellectual disabilities, and measures to increase labour force participation.

C. Approaches to employment support for people with intellectual disabilities

It is worth noting at the outset of this review of approaches to provision of employment supports and services that there are people with intellectual disabilities employed in the mainstream or open labour market without attachment to any particular type of employment support or service. They may also receive some degree of disability related support in other aspects of their lives. Thus, while what follows is a review of employment services, it is important to note that some people with intellectual disabilities are employed without engaging these supports, or have limited need for ongoing connection to formal support systems.

A review of the literature and interviews with key informants reveals that a range of types of employment services are being accessed by people with intellectual disabilities. The most prevalent models of support are sheltered workshops, day programs (not an employment type per se but included here for reasons that will be detailed below) and supported employment. Other types of support that are used less frequently are workplace enclaves, mobile crews, worker cooperatives, social enterprise, self-employment and micro-enterprise.

Sheltered workshops

A number of terms are used in the literature and in practice to describe the places and activities that are referred to in this study as “sheltered workshops”. Some other terms that are used include industrial workshops, affirmative industries or variations on the themes of training, rehabilitation and vocational support. The literature generally defines a sheltered workshop as a facility-based program where adults with intellectual disabilities perform activity that generates some degree of revenue as an alternative to working in the community as a part of the general labour market.

Main features of a sheltered workshop are:

- Activities offered: work is typically easy to learn and perform and often repetitive. Examples include assembly, packaging, servicing, sewing, etc.;

- Work environment: facility based and organized around a hierarchical structure with people without disabilities in supervisory positions and people with disabilities performing the revenue generating activity;

- Wages: participants are usually paid below minimum wage—sometimes in the form of a stipend or training allowance (Migliore 2007; Migliore 2011).

The objectives of sheltered workshops range from long term care and occupational therapy to training and transition to the general labour market. Despite the stated purposes of training and transition, the literature on sheltered workshops finds transition rates as low as 1-5% (Migliore 2011). Sheltered workshops also show minimal effectiveness as sites for training in skills that are transferable to mainstream settings (Rogan and Murphy 1991; National Disability Rights Network 2011).

Although the number of people in sheltered workshops is declining, sheltered workshop enrollments continue to exceed supported employment—with data from the U.S. showing a factor of 3 to 1 (Wehman et al. 2003; Migliore 2007). Interviews with key informants for this study reveal that sheltered workshop approaches continue to exist, to varying degrees, in most jurisdictions in Canada.

Researchers have identified a number of factors influencing the choice of sheltered over integrated employment (Butcher and Wilson 2008, Migliore 2007, Migliore 2008). These factors influencing choices are important to consider in transition strategies. They include:

- security for individuals and families that comes with long-term placement in sheltered workshops versus precarious employment in the community;

- respite provided to families by consistent programming, compared to individuals’ often part-time and unpredictable employment schedules;

- perceived safety of sheltered environment relative to employment in the community;

- provision of transportation services often associated with sheltered arrangements;

- fear of loss of disability benefits when entering the labour force; and

- social environments provided by sheltered workshops.

Key informants for this study reported that demographic shifts are driving demand for services away from sheltered workshops toward integrated employment services. While many older families involved in building workshops continue to advocate keeping them open, younger people who have been included in the mainstream school system, and their parents, are more interested in competitive employment or mainstream community involvement activities.

Declining demand is cited as a primary driver of change and the phasing out of sheltered workshops. However, this is not an inevitable process. Key informants for this study report that in some jurisdictions providers of segregated services actively recruit clients by promoting their options in the school system.

While few studies continue to promote sheltered workshops as spaces for transition to paid employment, some suggest that transition to paid employment is not a realistic or desirable goal for people with intellectual disabilities. Alternatively, they argue that ‘transition to meaningful activity’ emphasizing community integration through recreation, volunteerism and social activity represents a more appropriate objective. These studies also suggest that sociability and belonging for this group can best be achieved on the limited scale sheltered workshops or activity centres provide. (Butcher and Wilson 2008).

Increasingly, both advocates and researchers are calling for an end to segregated practices of workshops because they contradict labour market policies for inclusion, have damaging effects on individual quality of life, reinforce poverty, and limit transition to other more inclusive opportunities (National Disability Rights Network 2011).

Moreover, segregated approaches appear to violate the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, ratified by Canada in 2010, which recognizes the right of people with disabilities to “the opportunity to gain a living by work freely chosen or accepted in a labour market and work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities.”

Moreover, research has found that given the opportunity people would prefer to work outside of facility based programs. This research found this preference regardless of severity of disability or other demographic factors such as gender, time spent in workshop, residential status or location. Individuals and their families were also more likely to prefer work outside of the workshop if they had a previous, even if unsuccessful, work experience outside of the workshop (Migliore 2007; Zimmerman 2008).

Key informants report that while there is growing demand for alternatives to sheltered options, some key challenges are preventing an effective transition to mainstream employment:

- Early legislative and policy efforts to close or regulate sheltered workshops in the 1980’s led activities and work tasks being performed at segregated centers to be described as ‘training,’ ‘occupation’ or ‘activity’—sometimes with associated time limits and other requirements but often with little change to the material practices and compensation.

- Sheltered employment can encompass a diverse range of services and supports which are being tracked and reported by funders as employment outcomes. This keeps the service delivery structure and sheltered focus in place.

- Funding policies often provide financing only for very specific services, and do not provide for transition-oriented activities. This can stand in the way of transitions from sheltered workshops to integrated employment services.

- Bringing an employment support focus to sheltered programs can initially be seen as a duplication of services already available through other government agencies/ departments. This removes the policy and funding incentive for sheltered workshop providers to make the transition to mainstream employment options.

‘Day programs’: Training, life-skills and activity centres

Activity centres, sometimes called ‘day programs,’ training centres or life-skills centres are another dominant model of day support accessed by people with intellectual disabilities. They are generally facility-based programs that provide recreation and leisure as well as life-skills and vocational related training for people with intellectual disabilities. Their objectives are often described as being quality- of-life related.

While they are not an employment service model, per se, centre-based activity and day programs often serve people who have previously been in sheltered workshops or who might otherwise be involved in employment activities. Key informants for this research indicated that in some jurisdictions the closure or transitioning of sheltered workshops resulted in an increased focus on social and recreational activities offered by or based out of these activity centres. Some activity centres are found to function much like sheltered workshops in that they may accept packaging or manufacturing contracts which are fulfilled by the program participants although employment and training are not the primary objective. In some cases, people who are involved in employment may also be accessing the services of activity centres during times that they are not working.

Increasingly, day programs focus on community integration through individual or small group activities while using the centre as a ‘community hub’ or meeting place between activities. These activities include volunteering, recreation and leisure and other community involvement activities. Day programs and activity centres are widely available and accessed in most all jurisdictions across Canada.

Key informants for this study report that as sheltered workshops have been closed transitions have more often been focused on centre-based day programs than on labour market inclusion. More emphasis is being placed by providers on social and recreational programming than on employment related programming. The significant growth of volunteering activities was a recurrent theme among key informants in this study. Indeed, informants report that policy guidance and service descriptions for funded programs point to “volunteer work experience” as suggested outcomes for community involvement supports. A ‘drastic rise’ in volunteer work placements in the private sector through these programs was also reported. This was cited as problematic because of its effect of diminishing paid employment opportunities for all people with intellectual disabilities, lowering expectations and devaluing the economic contributions of people with intellectual disabilities. As one provider commented:

“Once an employer has accepted a volunteer placement of a person with an intellectual disability to work without pay it is nearly impossible to turn that employer around to hire someone with a disability for pay.”

Thus, at the service delivery level there is a clear tension in objectives between social and community integration through volunteer experience and a focus on employment outcomes. While some may suggest that volunteer experience is a stepping stone to ‘real work for real pay’ the evidence does not bear this assumption out. Sheltered workshops are closing or transitioning in many cases to models of day support that reproduce labour market exclusion. There is undoubtedly benefit to individuals of increased social integration that comes from such transitions in some, but not all, cases. However, there is immense lost opportunity for economic participation and security for people with intellectual disabilities because of a lack of clear policy and funding goals that establish employment outcomes as a priority.

Supported employment

As a service model supported employment grew out of dissatisfaction with the sheltered workshop system among people with intellectual disabilities and their families and staff in the 1970s and 1980s. It expanded rapidly and though it continues to grow, its expansion has slowed in recent years (McGaughy and Mank 2001; Cimera 2006).

There are different models for supported employment that are used throughout the world and discussions about best practices continue within the field. A predominant definition of supported employment that is being used in the literature as well as in U.S. law is the following:

...competitive work in integrated work settings, or employment in integrated work settings in which individuals are working toward competitive work, consistent with the strengths, resources, priorities,concerns, abilities, capabilities, interests, and informed choice of the individuals. . . for individuals with the most significant disabilities;

(a) for whom competitive employment has not traditionally occurred; or

(b) for whom competitive employment has been interrupted or intermittent as a result of a significant disability; and who, because of the nature and severity of their disability, need intensive supported employment services (McGaughey and Mank 2001).

Approaches to supported employment have in common, the provision of a range of supports to an individual with a disability to facilitate community employment for competitive wages. Supports can include but are not limited to:

- • training/pre-employment services: effective practices ensure that training is time limited and based on a curriculum; • job development, job search and placement services; • job coaching: on the job training and skills development; • retention / maintenance supports; and • ongoing long term employment supports.

Wehman et. al (2003) have developed a set of quality indicators for supported employment that are in use in the field as a technical capacities resource developed by the U.S. Department of Labour and Office of Disability Employment Policy. For more information see Appendix A. A further development of the supported employment model known as “customized employment” emphasizes indivi - dualiza tion of the employment service and the role of the provider in negotiating interests of job seeker and employers (Griffin 2008; Wehman et al. 1987; McGaughey and Mank 2001).

Studies of quality of life have found significantly higher quality of life scores among people with intellectual disabilities in supported employment than people in sheltered workshops, non-work day services and unemployment (Beyer et al. 2010, Eggleton et al. 1999). People employed through supported employment, regardless of severity of disability, on average earn 3.5 times the earnings of people in sheltered workshops. Over a period of 25 years in the U.S., sheltered workshop wages increased on average $0.19 USD/hr while average wages through supported employment increased by $5.36 USD/hr (Cimera 2010, Migliore 2008, Conley 2003).

Research also finds that supported employment is a good investment for taxpayers. Over twenty studies indicate that every dollar invested in provision of supported employment services saves more than that in reduced social security spending and the cost of alternative placements. Costs of providing supported employment over one employment cycle are also lower than those generated by participation in a sheltered workshop for the same period (Cimera 2008).

Key informants for this study identified a clear policy trend in most jurisdictions toward supported employment services being offered generically to either all persons with disabilities, or to all persons with barriers to employment (addictions, mental health, new citizens, disabilities). Agencies traditionally serving people with intellectual disabilities have either been required through policy or through funding model viability to expand their mandate to serving all people with barriers. There is also an identified shift by funders at both the provincial/territorial and federal level toward a streamlined or ‘one-stop-shop’ approach, which informants identify as posing new barriers for people with intellectual disabilities.

Informants reported that it is a challenge for generic employment services providers to be responsive to the particular needs of people with intellectual disabilities. Even where there have been focused efforts at developing these capacities, it was reported that people with intellectual disabilities were largely being left behind. Some efforts at increasing responsiveness of generic services have involved training/capacity building for intake and service coordination, and training for direct staff to recognize people with intellectual disabilities as capable of employment. There also need to be clear incentives to provide services to people who may require a greater amount of support. In most cases these appear to be lacking.

Depending on the funding model, there is an incentive to “cream” or “skim” employment candidates who require less time/resource for placement. This is particularly evident in jurisdictions where employment services are funded based on an outcomes approach that pays service providers for successful placements over a defined duration of time. Agencies are more inclined to serve people who are more likely to be profitable to them, as there is a disincentive to accept clients who may require more significant support.

Moreover, under a generic funding model based on securing employment placement outcomes, agencies traditionally mandated to provide employment support to people with intellectual disabilities find it necessary (or are required) to expand their employment supports to all groups of people with disabilities in order to make the funding model viable and to continue providing employment support to people with more significant needs. As a result, these agencies are only able to serve people with intellectual disabilities by opening their doors to job seekers with a range of barriers. The decision to do so is determined to a great extent by the values base and philosophy of the organization. Service providers that have a history in providing employment supports to people with intellectual disabilities will be driven to continue providing these services even if the funding model means that there will be a financial disincentive to do so. Other providers are not likely to take on the risk or financial disincentive involved in providing support to people with intellectual disabilities under this model.

A ‘one stop shop’ approach was identified by some informants as posing a significant barrier to providing supported employment responsive to people with intellectual disabilities. For example, streamlining and centralization of service coordination (i.e. “case management”) and assessment services can compromise the supported employment model for people with intellectual disabilities as such systems tend not to account for the extended period of relationship building and assessment of job needs they often require.

Where service providers have transitioned from sheltered workshops and day service models to supported employment key informants suggest they have faced major challenges. The traditional focus on sheltered workshop, centre-based programs or community integration activities with a volunteer emphasis is often at odds with the skills and culture necessary for effective employment support. These skills often involve business development and networking, outreach, communications and marketing. Informants also suggest that they face challenges in attracting and retaining employees with the appropriate skill set to work in supported employment services. Knowledge about job counselling and readiness, outreach to and working with employers, on-the-job support, developing capacities of co-workers, and labour issues tend to be lacking among support workers trained under a social service model (developmental services worker, personal support worker, social worker, community support worker, etc). As well, human resources and contracting policies are often not conducive to recruitment of employees with the needed skill-set. Overall, informants observed that while day program providers may wish to transition to supported employment services, they often lack the knowledge and tools necessary to make the change.

The research demonstrates that supported and customized employment are most effective in advancing labour market inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities. However, the disability- specific and generic employment services delivery systems do not appear to currently have clear policy guidance or funding to make this shift in respect of people with intellectual disabilities.

Other approaches to employment support: Enclaves, mobile crews, worker cooperatives, social enterprise and self- employment/microfinance

Other models of employment support that are used less extensively in Canada are reviewed below. These include workplace enclaves and mobile crews—variations on the model of sheltered workshops that remain in use to a limited extent in some jurisdictions—worker cooperatives, social enterprise, self-employment and microenterprise.

Workplace enclaves / mobile crews

Workplace enclaves and mobile crews are variations on sheltered employment that see groups of people with intellectual disabilities either working together as an enclave within a mainstream workplace or operating as a mobile business to fulfill contracts within the community. Common examples of workplace enclaves are mail rooms or shredding, stuffing or sorting operations. Examples of mobile work crews include janitorial or landscaping contracts.

Enclaves did not turn out to be a successful model in most jurisdictions and are less common today because of low outcomes for wages and social integration.

These models in many cases have coexisted in cooperation with either sheltered workshops or sometimes as a part of a supported employment program. During early efforts at sheltered workshop closures and conversions there were attempts to set up enclaves and work crews in order to transition people away from the workshops. Enclaves did not turn out to be a successful model in most jurisdictions and are less common today because of low outcomes for wages and social integration. Mobile work crews continue to a greater extent than enclaves though there is scarce evidence of wage outcomes that approach minimum wage.

While support and delivery models vary, some common characteristics of mobile crew or enclave employment are:

- An agency holds the contract for the work;

- Workers are employees of and/or paid by the agency;

- Workers are supervised by the agency;

- ‘Job sharing’—two or more workers share a position and are paid a portion of the wage for that position;

- Compensation is usually sub-minimum wage;

- Workplace is separated from non-disabled employees of the company;

Worker cooperatives

Worker cooperatives also stemmed out of efforts toward closure and transition of sheltered workshops in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Like enclave and mobile work crew employment, there are a variety of models that fall under the label of worker cooperatives. Also similar to enclave and mobile work crew employment they involve people with intellectual disabilities working together as a group—often to complete contracts that might have otherwise been completed by sheltered workshops.

In principle, worker cooperatives differ from other similar models in that they are worker controlled and owned. While many elements of these cooperatives replicate the sheltered workshop structure, the work relationship is redefined to return control and revenue to the workers involved. Numerous safeguards are necessary to ensure informed decision-making and control on the part of individuals who create the cooperative.

In the limited examples for which information is available, the financial benefits of the cooperatives rarely exceed the equivalent of minimum wage but have provided better financial outcomes than sheltered workshops. Worker cooperatives have been used as a transition strategy for closing sheltered workshops in order to provide an opportunity for people who had long worked in the workshop conditions and desired to continue working under a similar structure. In one study of a set of cooperatives that had been created in order to transition a sheltered workshop, the cooperatives have since been consolidated and progressively discontinued as the original workers age and retire. An interesting additional note is that organizations that transitioned the contracts completed by workshops to worker cooperatives observed an increase in productivity for the work being completed. The changes to incentives to work and greater autonomy over the work were seen to be behind this shift. (Maule and Crawford, 2000).

Social enterprise

Social enterprise is an emerging alternative to competitive employment involving small-scale businesses that seek to employ people traditionally disadvantaged in access to the mainstream labour force. Social enterprises involve the continuation of an enclave or sheltered model, in that the business is socially purposed to employ people with disabilities or other barriers. In comparison with sheltered workshops, they involve a greater degree of individualization, autonomy and community involvement. Examples of some businesses created under this model include catering companies, coffee shops, cleaning and maintenance, lawn care, etc.

As businesses, social enterprises are often subsidized by fundraising efforts or through other parts of the operations of a supporting organization. Social enterprises have become more common in recent years—especially among the community of people with mental health disabilities but also as businesses exclusively for people with intellectual disabilities. Like the preceding types of employment, social enterprises have often been created as a way of transitioning people from sheltered workshops.

Self-employment and microenterprise

Self-employment and microenterprise are employment strategies that are also used by people with intellectual disabilities. While the range of practices varies depending on the person, their interests, business model and their need for support, the most common considerations for self- employment do not depart from those for people who do not have a disability. The basic steps include developing a business plan, obtaining the required skills, securing start-up capital, implementing the business plan and expanding the business.

The role of supports for self-employment for a person with an intellectual disability is similar to the role played in supported employment. The skills that are needed include task analysis, skills training and ongoing provision of needed supports (Crawford, 2006). Considerations for best-practices and quality in self-employment are similar to those for worker cooperatives in that care must be taken to ensure the person starting the business is informed about and controls as many of the decisions about the business as are possible and desired and that the initiative is not being driven by an agency or staff person. Other best practices involve maximizing the use of generic resources that are available and engaging supports from the business community wherever possible before using agency and paid-staff supports. It is also important to fade agency supports as appropriate to enable the greatest degree of autonomy for the individual and their business. Connections with mentorship opportunities and generic networks of entrepreneurs increase the degree to which self- employment leads to community integration.

In the limited available research, self-employment has not generally resulted in financial outcomes comparable to minimum wage; however, there are examples of businesses that have experienced great success. While not nearly as extensive as other models of facilitated employment support for people with intellectual disabilities, self-employment is an attractive option for many. Self employment and microfinance are also especially relevant in rural areas or areas where job opportunities are limited (Kendall, et al. 2006; Conroy et al. 2010).

Summary

This section has described the range of employment- related programming targeted to people with intellectual disabilities, and has outlined research findings about their relative effectiveness in advancing labour market and social and economic inclusion. Three main conclusions can be drawn from the analysis.

First, it is evident from the research that sheltered employment and centre-based activity programs remain the primary service delivery structure for people with intellectual disabilities, and they deliver the poorest outcomes for individuals on any social or economic measure. The research identified a wide range of other approaches to employment support for people with intellectual disabilities. They vary substantially with respect to the extent of community integration they enable and the extent of labour market inclusion they are able to achieve.

Second, efforts to transition from sheltered employment models appear to often result more frequently in social and community integration than labour market inclusion. Many are transitioning from sheltered workshops to a lifetime of ‘volunteering’ in their communities. Others make the transition from sheltered employment to other enclave-based employment opportunities—a few of which may approach minimum wage or better, but restrict their access to a greater range of opportunity in the labour market. For example, many people with intellectual disabilities appear to be transitioning from sheltered employment to mobile work crews, worker cooperatives or social enterprise. Self-employment and microenterprises are promising alternatives for some individuals, but appear to be lacking the policy direction and investment to bring them to a more significant scale.

Third, while research demonstrates that supported employment does result in labour market inclusion and significantly improved quality of life outcomes, there appear to be significant challenges in transitioning to this model in the absence of a clear policy framework and investment strategy. The ongoing use of sub-minimum wage compensation for individuals working in economic enterprises suggests a form of financial exploitation of a targeted population that should not be allowed and is certainly inconsistent with minimum wage standards, domestic and international law, including the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Finally, it is important to note that many people with intellectual disabilities are working and have jobs with employers in the regular labour force independent of any facilitated employment service. It may be that they have accessed employment supports and services and are no longer in need of any significant level of support or interventions or they may have obtained employment independent of any employment supports altogether. These workers may also be accessing other disability related supports for other aspects of their lives.

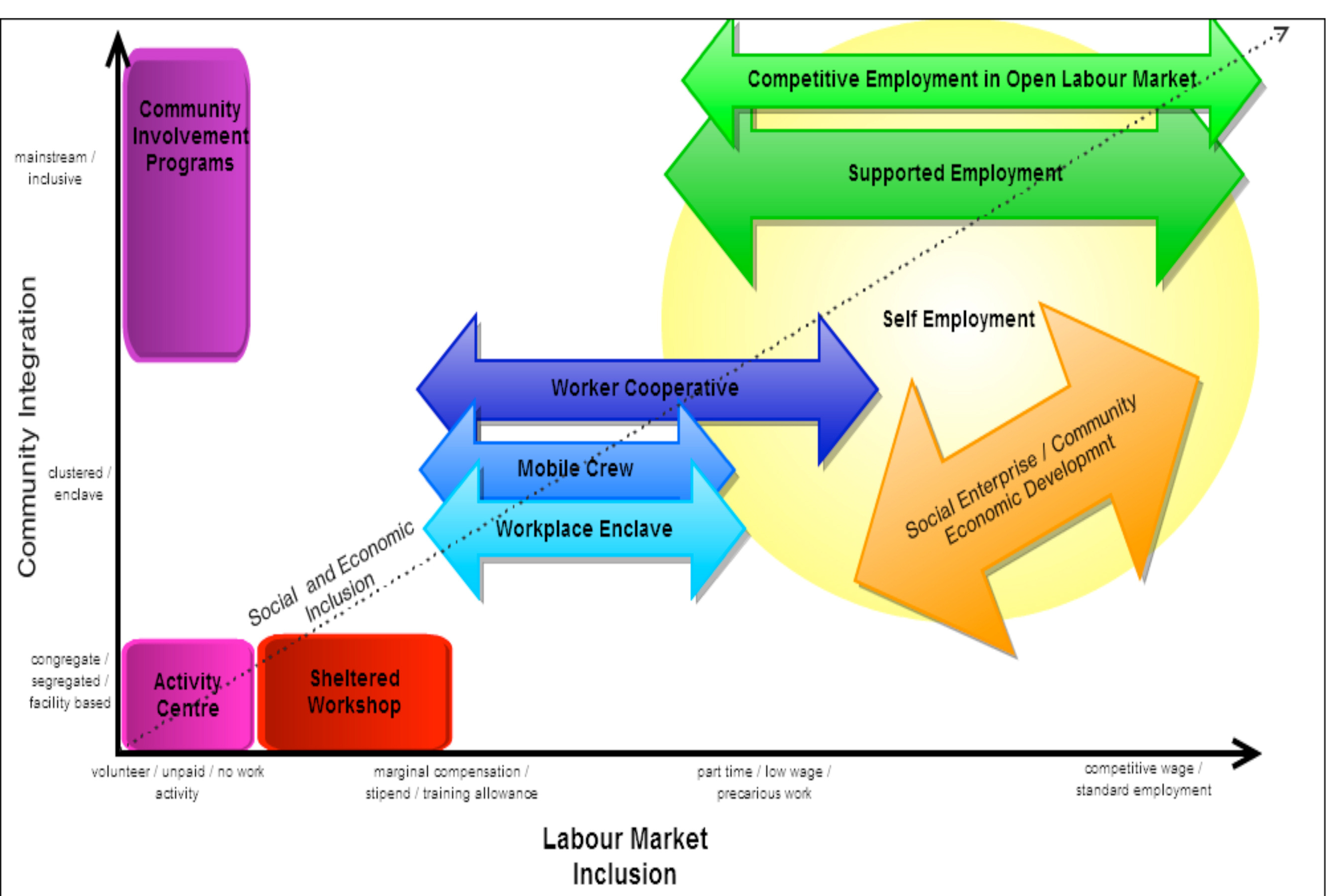

Figure 1 plots the different approaches reviewed above according to three vectors or dimensions of inclusion identified through the research literature:

- The vertical axis represents the community integration dimension of the activities enabled through the option – from centre-based/ segregated activities, to socially-integrated, community-based activities.

- The horizontal axis represents the extent of labour market inclusion – from options that provided minimal or no compensation to those that provide a living wage and benefits.

- The third dimension of the framework, running diagonally, signals the extent of social and economic inclusion that any particular option provides.

The Figure points to the relative impact of the different approaches in achieving the policy goal of labour market and social and economic inclusion. Supported employment and self-employment show the most promising outcomes for labour market inclusion and the highest degree of community integration. Other approaches such as worker cooperatives, mobile crews and workplace enclaves show slightly greater potential for labour market inclusion and community integration than sheltered workshops but cannot achieve the extent of social and economic inclusion that supported employment and self-employment provide.

The analysis in this section points to the importance of plotting a clear trajectory from sheltered employment to supported and customized employment options for people with intellectual disabilities. The next section points to effective practices for making this trajectory possible.

Figure 1. Community Integration

D. Effective practices in transitioning from sheltered workshops to labour market inclusion

Research literature on effective practices in transitioning from sheltered workshops to labour market inclusion stems mostly from the U.S. where a strong body of research and practice has been developed through their experience with “Employment First” initiatives and other transition oriented activities. The literature identifies a number of success factors making transitions possible. Some enabling factors include: employment first initiatives that are backed by clear policy and government priorities; establishing a system-wide goal of transition that provides flexible funding and policy direction; supporting leadership development among key stakeholders; developing a strongly connected network of stakeholders with a shared values base around employment; fostering leadership among agencies through support for innovation in service delivery, opportunities for collaboration and sharing of knowledge and best practices; providing training opportunities and technical supports for staff; and measuring and reporting outcomes to track progress and needed improvements (Hall et al. 2007, Wehman and Revell 2005, Hagner and Murphy 1989, Hall et al. 2011, Niemac et al. 2009, McGaughey and Mank 2001).

This section consolidates findings from the research literature and key informant interviews into seven main factors that enable governments and service providers to transition from sheltered employment to supporting labour market inclusion, and points to a range of good practices in doing so:

- making ‘Employment First’ the focus: system- wide employment focus for community supports for people with intellectual disabilities;

- awareness and leadership among parents and educators;

- building capacity of service providers;

- availability of long term employment supports;

- knowledge transfer and innovations;

- enabling income security systems;

- focus on employers as champions.

Making ‘Employment First’ the Focus

“Employment First” policies are a recent policy direction for day and employment services provided to people with intellectual disabilities. “Employment First” means that for government funded day supports for people with intellectual disabilities, employment is the first and preferred outcome. This approach has been adopted widely in the U.S., in particular in California, Washington, Minnesota, Indiana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Iowa, Rhode Island, Nevada and others (See Box next page). These policies have proven to be a singularly important factor in driving the transition from sheltered employment to labour market inclusion.

For example, Washington State reported in 2008 that 87% of people with intellectual disabilities receiving employment and day supports participated in integrated employment (Butterworth, et al., 2010). Newfoundland and Labrador has a policy framework that favours employment, British Columbia has adopted an employment focused policy and stakeholders in other jurisdictions are actively seeking such a policy framework with their provincial / territorial governments.

Key informants identified the importance of clearly defining employment outcomes as a focus. Policy initiatives do well when they define “what employment is, and what it is not.” This was identified as a good starting point for dialogue among stakeholders about transition from sheltered employment services to labour market inclusion.

Effective practices that aid the transition to an employment focus include:

- In policy development initiatives, early dialogue between stakeholders about “what is, and what is not employment” creates a common language and set of starting assumptions. Acceptance of a common working definition of employment is a positive first step;

- A leadership role from the disability and advocacy community;

-

‘Employment first’ policies or employment focus for social services delivery have been effective where they begin with discussions between stakeholders and government about employment. These can include forums, workshops, discussion papers and conferences with a goal of reaching clarity and common language around employment and training services;

U.S. ‘Employment First’ Policy Initiatives

- In the U.S. a number of States have adopted Employment First initiatives to focus on integrated employment for people with intellectual disabilities.

- Tennessee, Washington, California, Indiana, Minnesota, Georgia, North Dakota, Wisconsin, Missouri, North Carolina, Iowa, Rhode Island and Nevada have all established or are in the process of developing Employment First initiatives.

- These policies have a clear impact on achieving high outcomes for people with intellectual disabilities. In 2008, Washington State reported that 87% of people with intellectual disabilities receiving employment and day supports participated in integrated employment.

- While approaches to “Employment First” initiatives vary, they share a commitment of principles, policies and practices to achieving integrated employment for people with disabilities.

- Generally, adopting an Employment First approach means that for State funded services for people with intellectual disabilities, integrated employment is to be the first and preferred service option.

-

Nationally, States have been supported by policy change and infrastructure grants to support Employment First initiatives:

- The 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act enhanced employment possibilities for people with disabilities and paved the way for Olmstead v L.C 1999—a landmark community integration decision by the Supreme Court.

- In 2001, regulations governing state Vocational Rehabilitation Services programs redefined “employment outcome” to mean an individual with a disability working in an integrated setting removing placement in segregated/sheltered settings as an approved outcome for services.

- Since 1999, The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has provided Medicaid Infrastructure Grants (MIG) to support states move to competitive employment for people with disabilities. As of 2011, 42 States and the District of Columbia are participating.

- Other initiatives to support states in providing supported/customized employment services have been administered through the Department of Labour Office for Disability Employment Policy by funding demonstration projects and technical assistance centres.

- Tools to assist in transformation to an employment focus include: education and awareness activities about how to transition to supports for employment; initiatives to fund pilot projects for agencies transitioning to employment focused services; innovation funding; clear outcomes and quality of life indicators for service evaluation; contract monitoring by funders; and, prioritizing provisions in funding agreements to favour an employment focus.

Awareness and leadership among parents and educators

High expectations among parents and educators are essential to shifting the demand for employment support options from sheltered workshops and centre-based volunteer activity programs to labour market inclusion. Extensive research points to the importance of early planning for school to work transition for students with intellectual disabilities, and to high expectations of their parents and teachers for labour market participation. Key informants pointed to the following kinds of initiatives to promote awareness and leadership:

- Engaging families to develop high expectations and support for school to inclusive post- secondary education, training and employment;

- Fostering system-wide adoption of school to work and post-secondary to employment transitional planning;

- Increasing opportunities for working with the education system to encourage students with intellectual disabilities to pursue summer employment through a supported employment model, which has been shown to have positive outcomes on labour force attachment.

- Developing a cross-governmental agenda to advance transitions from school to employment – to address jurisdictional funding issues between ministries (i.e. employment, education, and community services)

Building capacity of service providers

The research literature and key informants emphasize the importance of sheltered workshop and day program providers building new capacities if they are to transition to providing employment- related supports that result in labour market inclusion. Good practices pointed to include:

- Changes to college and training curriculum for direct service workers to include an employment focus or specialization:

- Employment specialization is not widely available in training curriculum for direct service workers but some jurisdictions have begun efforts to develop courses and training opportunities with a focus on employment support;

- Key informants report that inclusion of an employment focus or specialization into the social work and developmental service worker curriculum has the added advantage of building greater variety and career advancement opportunities into the field of community services;

- Inclusion of an employment support focus also results in labour market flexibility as direct support workers can transfer this skill set to career opportunities beyond developmental / community services.

- Policies for social / recreational or community involvement programs limiting volunteerism to typical volunteer placements in the not-for-profit sector. This was cited as not only a values-based decision but also as a practical consideration in order to avoid confusion among employers;

- Where work experience without pay is pursued as a means to paid employment, providers noted that it is important to discuss timelines and expectations with employers. These safeguards are necessary to keep the intended outcome of paid employment in the foreground;

- Some organizations have incorporated supports for social and recreational activities into employment support models in order to ensure continuity of support. This has aided transition due to the increased sense of security for families, and continued respite;

- Some providers report that they establish a ‘firewall’ between social / recreational activities and employment services in order to maintain focus on employment. Other services and supports continue to be available to an individual who is pursuing or has obtained employment but those services focus on employment-related training and skills development such as job retention and advancement. This offers security to individuals and families without losing or compromising the focus on employment.

Availability of long term employment supports

Key informants stressed the importance of longterm, non-time-limited supports in enabling transition from sheltered workshops to models of employment support that advance inclusion. This needed provision is not available in most jurisdictions.

Only one jurisdiction, Newfoundland and Labrador, reported that employment supports could be provided without time limits over the long term.

Knowledge Transfer and Innovation

All jurisdictions reported some degree of positive transitions taking place from sheltered to integrated employment. Informants emphasized the need for and value of sharing these effective practices with other providers. They also pointed to the importance of raising expectations of parents and providers that employment and labour market inclusion was a viable option for those who had been attending sheltered employment and centre-based activity options.

Effective practices identified by informants to aid effective knowledge transfer include:

- Transition initiatives that provide funding for innovation of services through pilot projects and incubator funding have developed capacity and experience base for transitions. Clear expectations for funded projects through transition initiatives help to ensure that true innovation directed toward employment outcomes is taking place;

- When transition initiatives include a component of information sharing and regular meetings between funded projects as well as tracking and reporting there are better chances for a broader impact;

-

Some examples of educational and training projects under transition initiatives are:

- Production of a booklet about employment;

- Self-advocates talking to other people with intellectual disabilities about employment with a focus on income security benefits and fears about loss of benefits;

- Workshops for families;

- Training programs;

- Resources for employers;

- Organizational change seminars;

- ‘Learning trains’: training/informational sessions lead by employment service providers who have undertaken transition and demonstrated excellence in employment service provision. A rotating slate of presenters travel throughout the province to make presentations.

Incentives in income security systems

Informants from every jurisdiction reported that income security mechanisms need to be re-designed to address disincentives to making the transition to employment. These disincentives include: clawback mechanisms of disability related benefits for earnings and loss of health and other benefits; unstable changes in income can trigger rules related to income that result in overpayments, clawbacks and burdensome reporting; fear that working part time will disqualify the person from benefits because they are ‘proving that they can work;’ eligibility for other supports and services are tied to income and individuals risk losing those supports if earnings exceed that threshold.

Informants suggested the following proposals were needed to make the transition to employment possible:

- Improvements to earning exemptions, claw-back formulae and administrative mechanisms for reporting income have been made in some jurisdictions;

- Social assistance reform and poverty reduction strategies occurring in some jurisdictions are exploring disincentives to work within the income security systems;

- There is suggestion that barriers presented by income support mechanisms are not always based in fact and educational activities can help to illustrate benefits of working.

Focus on employers and business champions of employment

A focus on employers and their needs is an often overlooked component of labour market inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities. Some local efforts have shown results by developing networks of business ‘champions of employment’ who can assist in raising awareness among other employers of the benefits of hiring people with intellectual disabilities.

Informants pointed to the need for the following supports to enable employers to champion labour market inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities:

Access to information and assistance for providing job accommodations and on the job supports;

- Support to employers to undertake accessibility audits, re-design workplaces and job design, and to assist co-workers in developing skills and capacities in ongoing support;

- Identifying and connecting business ‘champions of employment’ who have recognized the benefits of hiring employees with intellectual disabilities;

- Employer-to-employer initiatives that work amidst existing networks such as chambers of commerce and local service clubs to share benefits of hiring people with intellectual disabilities. Examples of successful initiatives include Rotary employment partnerships, and a “Mayor’s Challenge” in Ontario driven by an expanding network of mayors committed to employing people with intellectual disabilities.

III. Policy analysis and proposed directions

This section addresses the following policy questions:

- What is the range of approaches currently being funded?

- What is the relative investment in this range of approaches?

- What is the effectiveness of federal sources in enabling transitions from sheltered employment to labour market inclusion?